ご無沙汰しております1, pardon the long absence in my writing. How have you been? A combination of personal circumstance and sickness—physical, spiritual, or some combination thereof—have kept me away from this project for far longer than I’d have liked.

But what better time to emerge from a dark hole than sometime after Easter weekend? Across cultures, resurrection has long been a theme tied to spring—the visible cycle of death and rebirth each year seemingly too tempting a symbol not to spin a story around. The Persian New Year Nowruz falls around this time, from which we derive the tradition of decorating Easter eggs. And the hare as a symbol of spring and fertility is thought to come from China (where the microseasons were created), from which the Easter Bunny may have found its start.

Historically in Japan, Shunbun (春分, the Vernal Equinox) was part of Haru no Higan (春の彼岸), the spring equinoctial week and sometimes called Haru no Nakaba (春の半ば). During this time, various Buddhist rites and ceremonies were carried out, and prayers for the start of the planting season were made. It was also one of the year’s designated times to travel to one’s ancestral home and visit the family grave site for cleaning and making offerings to the departed.2 Even with the Japanese public’s shift away from religious observation, it’s still common for households to partake in these grave visits, and do a big spring clean (a possible holdover from historic purification rituals for households).

Spring Cleaning is about fresh starts, and while I’ve been recuperating the seasons have continued turning. They move even when we do not, shifting and changing regardless of whether or not someone’s watching or writing about it.

So, with sincere apologies, rather than go backwards, we’ll look forward and pick back up from Kō 13 soon. However, I’d be remiss not to leave you with some interesting recommended reading on the microseasons we’ve missed. I am far from the only person writing in English about the microseasons and all the fascinating history, culture, and nature around them. In the course of this project I’ve had the pleasure to read a lot of great writing from others, so I thought that I could take this chance to share some of those with you all.

If you are curious about Kōs 8 through 12 (and I hope you are), then check these out, and given these writers a follow if you enjoy them.

Kō 8: “Peach Blossoms First Bloom"

Recommended: “First Peach Blossoms” by Mark S.

Season Words is a site with the stated mission “Connecting to nature through poetry and prose,” which I think they do very well. Their 72 Seasons section has posts about the microseasons that feature a mix of original and historical poetry.

(previous 72 Microseasons post)

Kō 9: "Caterpillars Become Butterflies"

Recommended: “Cultural Lepidopterology in Modern Japan: Butterflies As Spiritual Insects in the Akihabara Culture” by Hideto Hoshina

A longer, more academic piece, this article is a fascinating dive into the symbolism around butterflies in Japan, in particular how they often represent the soul, or spiritual power in popular media. Hoshina also makes the interesting observation that butterflies weren’t as culturally important in Japan historically when compared to fireflies and dragonflies. The journal that he wrote this article for also has a website: The Journal Of Geek Studies.

(previous 72 Microseasons post)

Kō 10: "Sparrows Build Their Nests"

Recommended: “House Sparrows Weather Winter in Urban Hollows” by Allison C. Meier

A change of direction (or rather, location) here as we swap the old city of Edo for the modern streets of Manhattan. NYC Microseasons is one of a few projects seeking to describe new microseasons suited for the local environment—much as the editor for the Japanese microseasons did when he adapted them from China’s 24 solar periods. In addition to great, thoughtful writing about how nature is experienced in an urban environment, the end of each entry usually has some great follow-up reading to check out.

A similar project, which rather than trying to adapt the microseasons 1:1 for their local environment instead uses the Japanese microseasons as a starting point for engaging with the nature around them, is

by Ann Collins. You can join Ann for a meditative walk in the North Carolina woods right here on Substack.There’s also the book Light Rains Sometimes Fall: A British Year through Japan’s 72 Ancient Seasons by Lev Parikian, which I haven’t yet read but intend to keep an eye out for at the library.

(previous 72 Microseasons post)

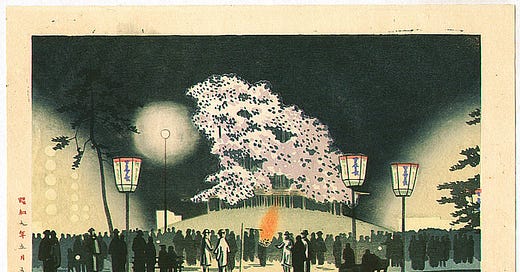

Kō 11: “Cherry Blossoms Open”

Recommended: “first cherry blossoms.” by Mark Hovane

The real challenge here was choosing just one source to recommend. There are so many authors, writing today and before, who have written many carefully considered words about Japan’s cherry blossoms. They are, after all, arguably one of the country’s most famous symbols.

I landed on this piece by Mark Hovane, who has lived in Kyoto since 1989 and is extremely well-versed in Japan’s botanical culture. His writings on his website Kyoto Garden Experience cover all 72 microseasons, and provide a perfect overview of each with additional insights from his expertise and lived experience. I’ve been reading it since I started this project, and it’s definitely guided my own writing.

Mark also offers bespoke tours of the city’s hidden garden treasures, should you find yourself in the area.

(previous 72 Microseasons post)

Kō 12: "The Voice of Thunder Speaks"

Recommended: “Raijin” and “Fujin” by Gregory Wright

Mythopedia is an online encyclopedia of the gods and legends that make up those shared stories about how the world works that we collectively call mythology. It’s as well researched as it is well organized and beautifully presented.

Their entries on the Japanese God of Thunder Raijin and God of Wind Fujin contain not only descriptions, but also their genealogy, background, and appearances in other media. We only briefly mentioned them in last year’s post, so I wanted to share a bit more of their story.

The Japanese pantheon of gods may not be as well known in the Western world as that of the Greek or Norse gods, but it’s every bit as rich and complex with its gods, heroes, and monsters. Mythopedia is a great resource for digging into the various otherworldly characters the often appear in our talks here about art and history, so well worth bookmarking.

(previous 72 Microseasons post)

And that brings us back up to the present! I hope that, when you have the space and time, you enjoy going through them and maybe reflecting on what nature’s been doing around you these last few weeks. For my part, I think I’m about back to full strength and excited to write some words of my own again.

See you next kō~

[Images & info courtesy of kurashikata.com, kurashi-no-hotorisya.jp, 543life.com, and Wikipedia except where otherwise noted]

Read go-busata shite orimasu, this phrase is mainly constrained to written communications

Japan does not inter bodies, with cremation being the dominant funerary method, and so grave sites are shared by a family line—wooden markers are added with each person who passes on

The other main time for these grave visits is, appropriately, during the autumn equinoctial week, colloquially known as Obon

I’m glad to hear of your healing. Thank you very much for sharing all these additional resources. Can’t go back, but we can continue moving forward - broken and renewed.

Thank you for recommending Microseasons, Iki! I hope you’re feeling strong and well. I’ve been busy settling into a new job, but I hope to join you back here at Substack soon!🌿