Japan's 72 Microseasons - #7+

Insects and Idioms

March 5 - 9

蟄虫啓戸

すもごりむし とを ひらく

Sumogori-mushi, to wo hiraku

“Hibernating insects open their doors"

(This is the second post about this microseason—if you missed the first one, you can read it here)

Underneath and around our feet, beneath our homes and throughout our gardens, in all the places largely unseen there thrives a tiny, flourishing world. This is the domain of the critters, the minibeasts, the creepy-crawlies. And no matter how we’ve tried to abolish it from “civilization,” it is never that far.

Insects on their own outnumber humans by something like a billion-to-one, accounting for 90% of all species on Earth. And that’s not even counting things like frogs, lizards, snakes, and worms. All of these are included in the Japanese word mushi (虫 or 蟲), and kō 7 is when they begin to wake up from their hidden winter slumbers. Dotted around forests and fields are small, mysterious holes in the ground—newly opened doors flung open to greet the spring weather.

I’ve always had an appreciation for those tiny bits of the wild assert themselves into an urban environment1. Where I grew up was very suburban and yet our home played frequent host to all manner of lizards, spiders, and bugs of all varieties. We encountered turtles in the road and snakes at our schools. It’s a reminder that we are a part of the world—that we exist within nature, not separate to it. Our habitats of concrete, metal, and wood may be bigger and fancier than a carefully dug earthen hole outside, but we share the same real estate.

Because we encounter them so frequently, often within our homes, our tiniest neighbors feature into many of our stories and sayings. So for this newsletter I thought we’d look at Japanese kotowaza (諺) and yojijuku-go (四字熟語). Kotowaza are your standard proverbs, aphorisms, and general bits of wisdom packaged in a catchy phrase. Yjijuku-go, on the other hand, are a bit more uniquely Japanese: they’re always made of four kanji characters (the 四字 part) that together form an idiomatic phrase (the 熟語 part) or metaphor. You’ll see.

Let’s start with some kotowaza first:

蓼食う虫も好き好き2

Tade kū mushi mo sukizuki

“Even bugs that eat weeds have their preferences”There’s no accounting for taste; to each their own

一寸の虫にも五分の魂

Issun no mushi ni mo gobu no tamashii

“Even a one-inch bug is 50% will”A cornered mouse will bite a cat; there’s plenty of fight in the small

虫の居所が悪い

Mushi no idokoro ga warui

”Things are bad in the bug place”3In an inexplicably bad mood; woke up on the wrong side of the bed

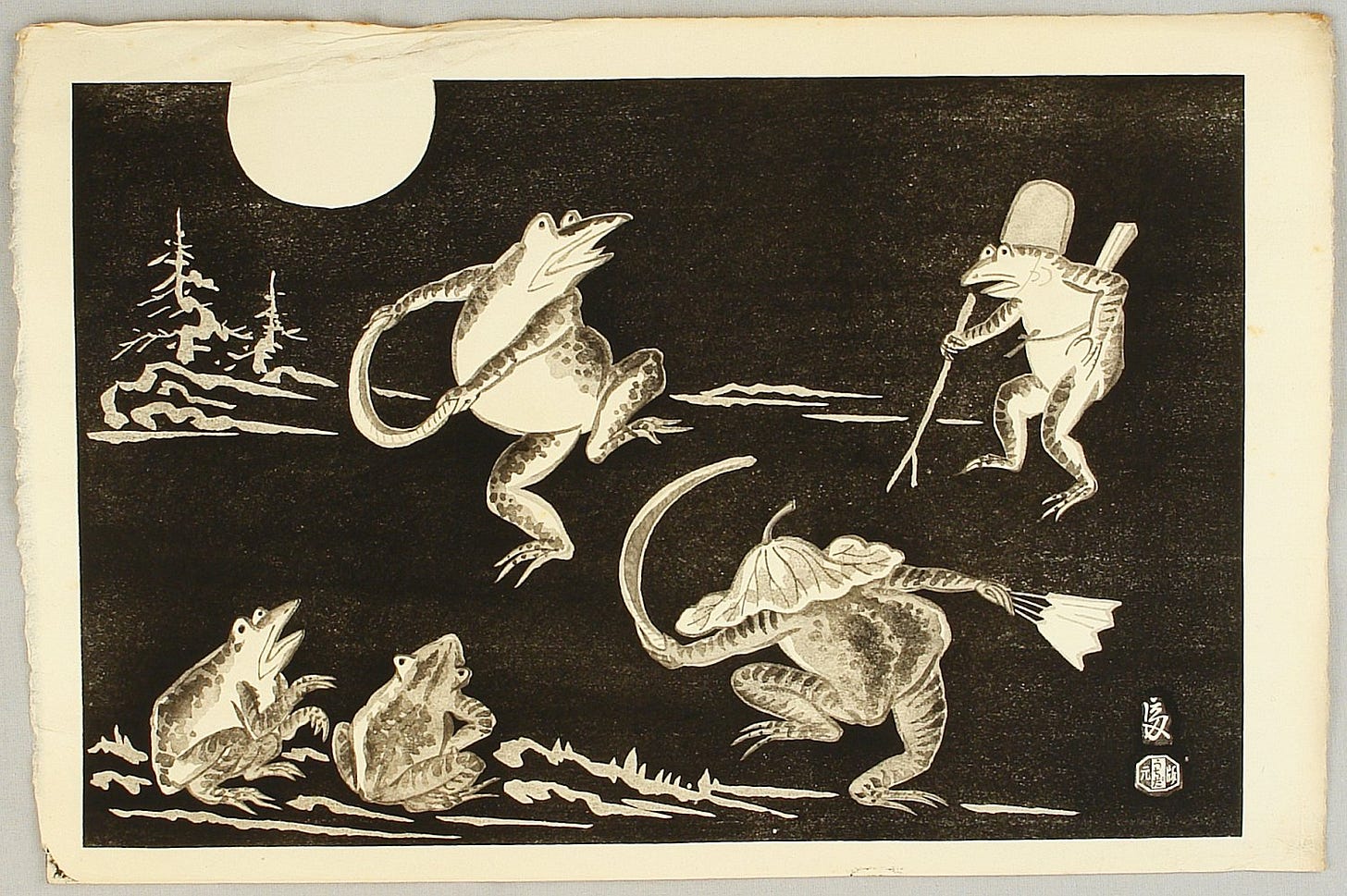

蛙の子は蛙

Kaeru no ko wa kaeru

”The child of a frog is a frog”Like father, like son; the apple doesn’t fall far from the tree

井の中の蛙大海を知らず

I no naka no kawazu taikai wo shirazu

”The frog in the well doesn’t know the sea”To be ignorant of the wider world; a babe in the woods

蛙の面に水

Kaeru no tsura ni mizu

”Water on a frog’s face”Water off a duck’s back

藪を突いて蛇を出す

Yabu wo tsutsuite hebi wo dasu

”Poke at the bushes and reveal snakes”Go looking for trouble; kick a hornets’ nest

盲蛇に怖じず

Mekura hebi ni ojizu

”The blind don’t fear snakes”Fools rush in where angels dare to tread

蛇足ながら

Dasoku nagara

Like legs on a snakeAn unnecessary addition

These types of phrases compare animal and human behaviors, or use them as examples, and the structures are familiar enough. So now let’s take a look at some four-kanji idioms involving creepy-crawlies:

彫虫篆刻 / chōchū tenkoku / “carving your seal onto a bug”

Something that is crafted or decorated down to the smallest detail; can also mean something that is overwrought or putting too much time into trivial details

蛙鳴蝉噪 / amei sensō / “frogs and cicadas buzzing”

A noisy, useless argument or pointless controversy.4

雲竜井蛙 / unryū sei-a / “(the distance between) sky dragons and well frogs”

A vast difference in experience, social standing, or knowledge.

螻蛄之才 / rōko no sai / “the talents of a mole cricket”

A jack of all trades but master of none. Mole crickets can fly, swim, run, dig, and climb trees, but aren’t the best at any of those skills.

蛇蚹蜩翼 / dafu chōyoku / “a snake’s scales, a cicada’s wings”

To mutually rely on each other—a snake needs its scale to move, but in turn the scales are moved by the snake

杯中蛇影 / haichū no daei / “snake shadows in your sake cup”

To be full of doubt or grow sick with worry only to find it was nothing.

There are thousands of these four-character idiomatic compounds, and they can lend as much color to everyday conversation as they can to erudite literature. The dictionary I used for writing this5 maintains a daily, weekly, and monthly search-interest ranking. The top searched for this month fits nicely with our theme: 鳶飛魚躍 (enpi gyoyaku), “falcons soar and fish leap” or, put another way, “all living things live best when they live according to their nature.”

Which is, naturally, what bugs do.

The ways that we choose to describe and depict things say a lot about our collective feelings around them. Whether something is welcome or not, whether something is dangerous or not, whether it’s to be emulated or avoided. Over the millennia that we have been developing our culture and civilizations, we have always kept an eye on nature—even the very, very small parts of it.

See you next kō~

[Images & info courtesy of kurashikata.com, kurashi-no-hotorisya.jp, 543life.com, and Wikipedia except where otherwise noted]

Except for scorpions, which I cannot bring myself to appreciate

There is actually a four-character version as well: 蓼虫忘辛 (pronounced ryōchū bōshin)

This one perhaps requires some supplementary explanation: in Chinese Daoist thought, there was a theory of three “bugs” that inhabited the body and accounted for certain urges, behaviors, and sicknesses that weren’t easily explained away or wholly out of character

The upper bug was responsible for headaches as well as attachment to money and material possessions; the middle bug was responsible for diseases of the organs as well as insatiable appetites for food and drink; and the lower bug was responsible for pains in the lower body as well as lustful behavior

Japan has maintained this body-bug-blaming in much the same way we might blame gremlins or other tiny critters for our irrational behavior (Japan’s bugs mainly live in the belly, and cause anger, hunger, and hanger)

A version of this that emphasizes that the bluster will soon pass is 春蛙秋蝉 (shun-a shū-zen), “spring frogs, autumn cicadas”

yoji.jitenon.jp

I loved this so much. It's a delight on its own, but also provides some really useful context in helping deepen my understanding of Kobayashi Issa's thousands of bug-related haiku. I wish I could read Japanese well enough to consult that dictionary.