December 17 - 21

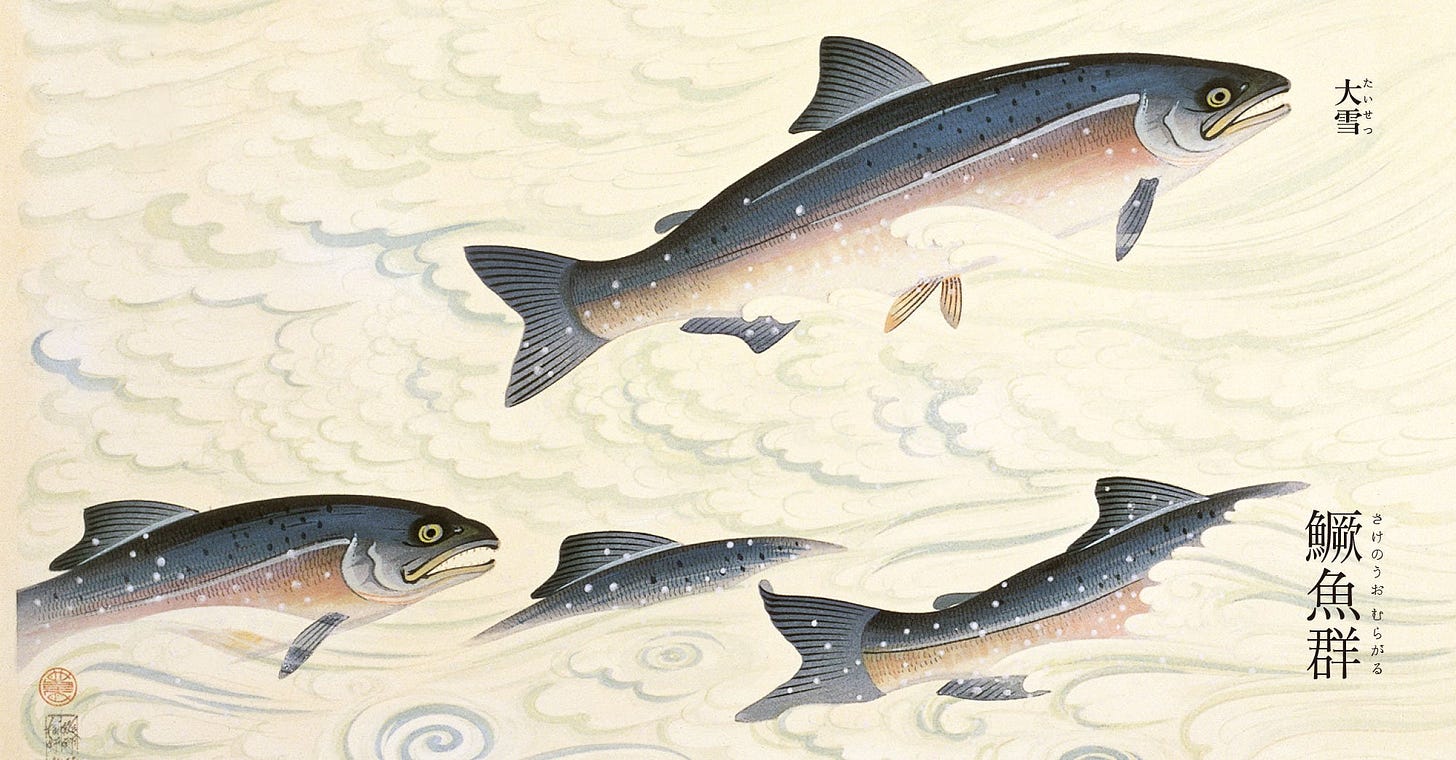

鱖魚群

さけのうおむらがる

Sake-no-uo muragaru

”Salmon gather back home1”

For many, the end of the year holidays are a time for coming home, for going back to where you started to think about where to go next. The same is also true for most salmon, although their specific holiday traditions are as yet not known to us.

A delayed post following the holiday rush! We undertook the unrecommendable task of moving into a new house 1 week before Christmas, but were in turn warmly rewarded by good, lively company in our new space on the big day.

Wherever it is that you call home, I hope you were able to journey there safely and spend this time with similarly friendly company along the way. And, with any luck, I hope that it was less arduous and life-threatening than that undertaken by salmon returning to the river they were born in to spawn new life. In a very literal sense, they must battle against the current to do so. A phenomenon that has long served as a symbol of single-minded perseverance in service of one’s goals2—in this case, the birth of the next generation.

Salmon (as opposed to what we call “trout”) spend their adult lives in the sea. Starting around September, they begin to make their way upstream towards the freshwater river they were born in, led by a keen sense of smell and arriving just in time to ring in the new year at home.

As single-mindedly focused on their destination as they are—fleeing predators and quickly lowering temperatures up north—salmon swim tirelessly and don’t eat during their journey. Because of this, they’re not typically fished during this season3, with autumn being considered the best time for fresh, fatty salmon, bulked up in preparation for the trip.

Instead, what’s eaten towards the end of the year is salt-cured and sun-dried salmon, called aramaki (荒巻)4. During New Year’s festivities, these are given to friends and neighbors, and offered to the kami Toshigami (歳神, lit. “years god”) in order to avoid misfortune and catastrophe.5

Indeed, how they’re eaten and where you’re eating it has an effect on what salmon is called in Japan. The main split is between sake (as named in this kō) and shake6. Both are written with the kanji character 鮭, but in general, sake refers to salmon that is living, raw (as in sushi), or presented whole; and shake is usually reserved for flaked or salted pieces. Both derive from the Ainu language, given the fish are natively found up north and formed a central part of their diet.7

One more word you might often see though is the English “salmon” (サーモン, pronounced as sāmon). Appropriately, this often refers to non-native fish, with the most famous being Aurora Salmon (オーロラサーモン), the brand under which Norwegian-farmed Atlantic salmon is known as. You’re also far more likely to see the word “salmon” on a sushi menu, if you see it at all. The reason being that salmon was not historically used as a sushi topping, given it’s far more prone to parasites than other fish. Japanese law requires that raw salmon first be frozen for at least 24 hours under -20° C (-4° F).

Obviously, this preparation was unavailable in 1800s-era Edo, so the fish was often alt-cured instead, leading to the aramaki tradition. This changed with the importing of foreign salmon, which had already been frozen beforehand and was thus safe to eat. Due to its high fat content that held up well under transport and remained tasty after thawing out, Atlantic salmon became the de-facto type for sushi. In this way, seeing sake, shake, or salmon on a menu can clue you in to what you might expect to appear on the plate.

Trout, incidentally, is called masu (鱒). Although, again, we are talking about the same family of fish here.8

While salmon themselves aren’t often caught and eaten during this time, this is the best time for fresh ikura (イクラ), salted salmon roe. Interestingly enough, the word ikura derives not from Japan, but farther north in Russia.

There doesn’t seem to be any other specific vegetables, flowers, or other produce related to this kō beyond the titular salmon, so instead let’s look at a couple of ways the Ainu have enjoyed eating this microseason’s star seafood:

Citatap - raw salmon meat and bone minced and seasoned with onion, herbs, and dried kelp

Cipor Rataskep - mashed potatoes with salmon roe

Cep ohaw - bone broth stew filled with chopped salmon, root vegetables, and fragrant herbs9

One can’t help but wonder if the salmon know what draws them out of the sea and back inland, or what they think as they spend months retracing a path taken years prior when they were smaller and younger. Do they feel nostalgic? Do they dread running into distant relatives? Do they anticipate the final arrival when they can safely rest and eat? Maybe the reason they head home is pure habit, but hopefully they find something good there nevertheless.

See you next kō~

[Images & info courtesy of kurashikata.com, kurashi-no-hotorisya.jp, 543life.com, and Wikipedia except where otherwise noted]

Wishing you and yours a very happy and restful holiday season!

I didn’t research as much as I should’ve before the Twitter post, so hadn’t noticed that salmon begin their journey upstream in September and its around this time that they’re finally ending it

The appropriate 4-kanji aphoristic phrase for this is 一心不乱, read isshin-furan

And luckily for them, the bears have mostly all gone to sleep for the winter

Sometimes also written as 新巻, with the kanji character for “new” instead of “rough, wild”

Why salmon for “avoiding” misfortune? The answer, as it often is, lies in Japan’s love of wordplay: the word for avoid is sakeru (避ける) which is homophonous with the word for salmon, sake (鮭)

Remember that Japanese pronunciation is mostly based in consonant-vowel pairs, so these are pronounced sa-ke(h) and sha-ke(h), respectively

In Ainu, they were called kamui chep (“fish of the gods”)

Much of the research for this kō was done on the impressive collection of sushi-related knowledge at sushiuniversity.jp, which has far more information on salmon in Japan as well as deep dives into nearly any topic you can imagine regarding the country’s iconic cuisine

This dish is thought to be the predecessor to one of Hokkaidō’s famous regional specialties: Ishikari Nabe

So inspired by your seasonal posts, and excellent research! And the little snippets of humor as well. Happy holidays, happy homecoming.

Brilliant.