November 27 - December 1

朔風払葉

きたかぜこのはをはらう

Kitakaze konoha wo harau

”Northern winds clear the trees”

Let’s open with a poem, although not one from Bashō, Buson, Issa, or Shiki1, but from the American poet Robert Frost, writing in 1923:

Nature’s first green is gold,

Her hardest hue to hold.

Her early leaf’s a flower;

But only so an hour.

Then leaf subsides to leaf.

So Eden sank to grief,

So dawn goes down to day.

Nothing gold can stay.

I think that the Four Great Masters of Haiku would have agreed heartily2 with the themes in Frost’s iconic poem about life and death and nature. Although Kō 54 at the start of November brought us maples turning to gold, in truth the brilliant colors of autumn are a last blaze of glory for leaves soon to fall.

Gradually, the land and air dry out, and strong, cold winds blow down from the mountains. These winds are called kara’kaze (空っ風), “emptying winds,” or kitakaze (北風), “northerly winds.” However, this kō names them as sakufū (朔風), an older term for these northerlies which points towards the end result: the character 朔 represents the new moon, a new period of time, and going back to where things started.

Even as this year’s leaves are being blown from the branches, the plans for next year’s leaves are already in motion within the wood. To grow something fresh, the old must be cleared away.3

How the kanji character for the new moon came to be associated with the northern direction is something of an interesting story in itself. In the sexagenary4 cycle of the Chinese Zodiac (called kanshi/干支 in Japanese), the first of the twelve zodiac animals is the Rat, who in the myth rides on Ox’s back until right before the finish line, jumping ahead to win first in the Great Race declared by the Jade Emperor.

Taking the honor of first in the race meant that Rat became first in the cycle, and thus came to be associated with the turning of the celestial clock5. This is also true of actual clocks, with midnight being “The Hour of The Rat.” Because the ordinal directions are also quite important in Chinese cosmology, directions were also assigned to the wheel, and Rat at the top came to represent north.

In the same way the Rat marks the start of the Zodiac cycle, and its hour the start of a new day, the new moon is the start of a new month (in lunar-based calendars, anyway) and, naturally, the first new moon is the start of a new year. And so, over time, the Rat’s connection to the North direction likewise became attached to the new moon.6

Thanks to this long linguistic journey, we could then interpret 朔風 to be “winds of the new year.” Of course, meteorologically they are also literally coming from the north.

Whatever you call them, as the season progresses these winds begin to pull all the red, orange, and yellow from the trees and scatter them to the ground, where they briefly serve as a vibrant carpet before returning to the earth to feed next year’s plants. This fallen foliage is called nozomiba (望み葉), with 望み being a word you can also use to describe looking out over beautiful scenery from on high.

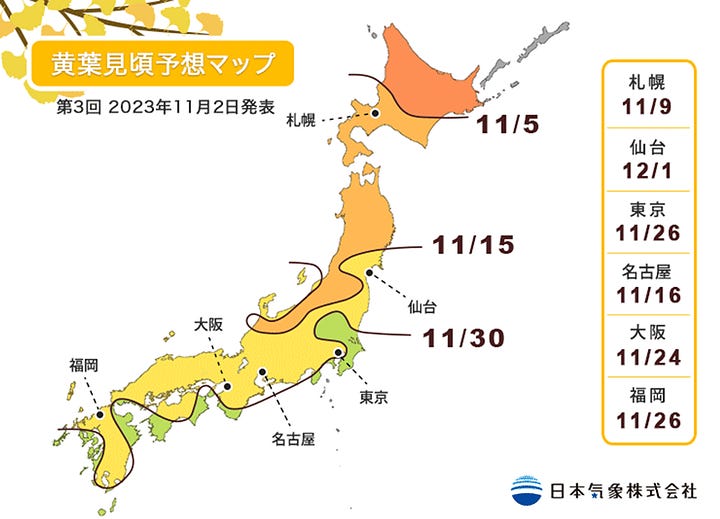

Of course, the cold front that fells fall’s leaves moves by degrees down the country, and for some places in Japan there’s still time yet for momiji-gari (紅葉狩り), “leaf hunting.” Just as with the cherry blossoms, there’s no shortage of maps, forecasts, and trackers to help guide people to the best spots at the best times. And certain places around the country are particularly famous for their autumn colors, such as Kiyomizu Temple in Kyōto.

If you do take some time to trek among the leaves—and I of course highly encourage you to do so, this weekend if possible—then you’ll need something tasty as a reward on your return. Perhaps I could make some seasonal suggestions?

● Seasonal vegetable

hakusai, 白菜, napa cabbage● Seasonal seafood

kamasu, カマス, barracuda● Seasonal (non-edible) plant

yatsude, 八つ手, fasti7

There are two concepts in Japanese art and philosophy that we’ve described and circled around quite often but never named. These are wabi-sabi (わびさび) and mono-no-aware (もののあわれ). The former can be described as “the beauty of quiet, subdued simplicity” and the latter as “an appreciation of the fleeting nature of life.”

Both can be understood firsthand by simply taking a moment to watch the leaves fall.

See you next kō~

I think it would be a nice little goal to reach 150 subscribers by the end of this year, so if you know someone who might enjoy learning esoteric tidbits about Japan in this way please feel free to put in a good word — we’re only 10 away at the moment!

[Images & info by kurashikata.com, kurashi-no-hotorisya.jp, 543life.com, and Wikipedia except where otherwise noted]

Sadly, even the most modern of them, Shiki, weren’t around for Frost’s lifetime—the last master passed away in 1901

Consequently, the harau (払) part of this kō’s name has two meanings: one is to prune (as in branches), and the other is to pay or settle a debt—both are a way of clearing out the ledger and resetting for something new, either leaves or more shopping

6o years, so calculated because each of the Twelve Zodiacs can further be assigned one of the Five Elements—earth, wood, metal, fire, and water—leading to Earth Rats, Fire Snakes, Water Dragons and the like

Because of this turning, the Year of the Rat is generally considered to be greatly auspicious, signifying great change and new beginnings—I’ll note that the last one was in 2020

The character was also shorthand for the new legal and fiscal year in Ancient China, which was famously bureaucratic

The English name is derived from the perceived pronunciation of the Japanese word hachi, meaning “eight” and a nickname for it is “Tengu’s Fan” (Tengu no Hauchiwa/天狗の羽団扇) after the similarity in shape to the mythical goblins’ trademark tool