Japan's 72 Microseasons - #22 & #23

"Waking Silkworms Eat Mulberry Leaves" and "Safflower Fields Flourish"

May 21 - 25

蚕起食桑

かいこ おきて くわを はむ

Kaiko okite, kuwa wo hamu

Waking silkworms eat mulberry leaves

May 26 - 31

紅花栄

べにはな さく

Benihana saku

Safflower fields flourish

For as long as we have been aware of the natural resources around us, humans have harvested and transformed them into something new. Oftentimes, this is practical: reeds into shelter, rice into food. But for almost just as long, humans have been using whatever’s at hand to create things that serve no purpose other than to be beautiful.

And if you wanted to create was a silk kimono dyed a striking red, you’d have the natural forces at work in these two kō to thank. Let’s talk about silkworms and safflowers.

[As a quick note: this post turned out a bit longer than usual, so it may cut off in some email programs! If it seems to end abruptly, open the link in Substack to view the rest]

The Silk Road—the network of trade routes that connected the East and West for centuries—is most often pictured as Chinese goods making their way to Europe, but Japan also participated (and benefited) greatly from the international connections. Passing through China and crossing the sea, a whole variety of exotic exports made their way into the young island nation. Perhaps the most enduringly significant in terms of impact to Japanese history was Buddhism, but the Road’s namesake product—and the wondrous insects that were key to its production—eventually led to an established domestic tradition of silk production.

Silkworms would become so important to Japan over the centuries they were cultivated1, that they were given the respectful honorific -sama when spoken about (蚕様) and counted as livestock, not insects2. In fact, an alternate name for this month in the old lunar calendar is Ko-no-ha-tori Zuki (木の葉採り月), meaning “the month where leaves are picked (for silkworms to eat)”3. Prior to World War 2, nearly 40% of Japanese households engaged in silkworm cultivation and Japanese silk exports accounted for around 60% of the world’s total production.

Silk is a fascinating natural textile, the kind of which only became possible by a combination of human ingenuity and animal behavior. Like many species of moth and butterfly, silk moths lay their eggs on one specific plant—in this case, the mulberry tree. Once the silkworms hatch, they will only eat mulberry leaves, and they do so with such vigor the sound of many feasting at once is said to resemble the sound of rainfall (called ko-shigure, 蚕時雨).

As they awaken during Kō 22, the rapidly growing silkworms eat without ceasing, day and night, and the quality and amount of silk produced depends entirely on how many fresh mulberry leaves they’re supplied with. Essentially, they need someone to attend them 24 hours a day to keep the buffet stocked up. The natural question would be why can’t they be left on a tree full of leaves to graze freely like cattle, and the reason is due to that same millennium-long history of cultivation. It’s led to an interdependence wherein silkworms bred for sericulture are unable to find and eat leaves on their own4.

Once harvested and processed, raw silk would be ready to dye into a striking color fit for a luxurious garment. A deep (and interesting!) topic that many others have written far better about, the history of dye-making is another in which humans have sought a way to bring something beautiful from the natural world into our everyday lives. It used to be that every shade of color had its specific origin in a plant, rock, or animal product, and benihana5, the dyer’s safflower, produced a color that became strongly associated with good fortune in Japan.

Like silkworms, safflowers came to Japan via the Silk Road, and similarly brought a good deal of prestige and prosperity as the country developed its own domestic industry for processing it into a fine, expensive dye. While most closely associated with a rich crimson red,6 the flowers start as a light yellow, and can produce shades of pink and orange depending on processing, repeated dyeing, and the fabric used. To draw out the trademark red, though, requires a time-consuming process utilizing only about 1% of the flowers’ natural pigments7.

This meant the dye demanded a high price, which brought with it a reputation of high-class exclusivity and, in its course, a connotation of good fortune. A bar of processed benihana was said to be worth 10 times more than gold during the Edo Period. Eventually, the highly demanded color began to find its way into more than just the clothes of the wealthy elite, but also shrines, good luck charms, and baby clothes, all said to promote a bountiful life and ward off misfortune.

During the height of benihana dye production, the prefecture of Yamagata in northern Japan emerged as the most well renowned place to get it from. It became so famous, so inseparably characteristic of the fashion and art of the time, that Yamagata Crimson was held up alongside Awa Indigo as one of the Two Great Dyes of the Edo Period (江戸時代の二大染料). Benihana remains the official flower of Yamagata, and festivals are still held there to celebrate this period when they bloom.

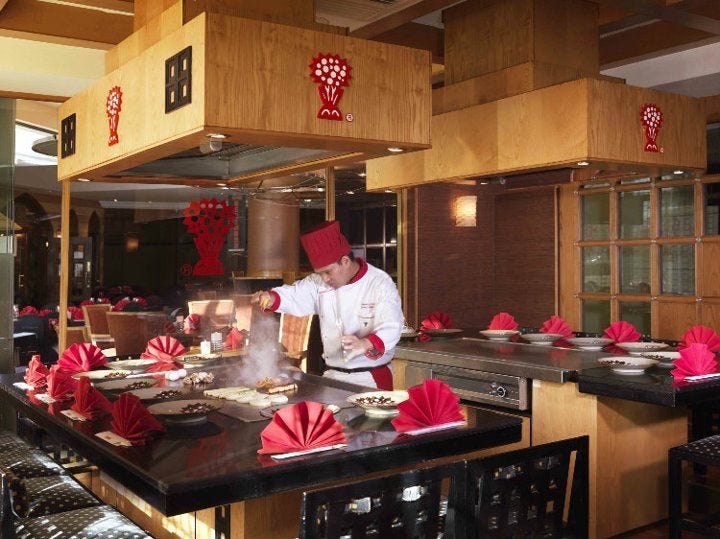

When not used in luxury dye-making, the plant has also been long used as a substitute for saffron8 and cooking oil. Speaking of, for some the word “benihana” may conjure images of fiery cooktops, onion volcanoes, and shrimps flipped into mouths, thanks to the popular chain of teppanyaki restaurants called, appropriately, Benihana. And although they have little to do with Japan directly (the chain was founded in New York in the 1960s), the trademark crimson color and flower itself are used in the theming:

Although likely not available at the showy dinner performances of Benihana, here are the seasonal items for these two kō:

● Seasonal flower

ajisai, 紫陽花, hydrangea● Seasonal seafood

kisu, 鱚, whiting● Seasonal insect

tentōmushi, てんとう虫, ladybug

● Seasonal produce

shiso, 紫蘇, perilla● Seasonal seafood

kuruma-ebi, 車海老, tiger prawn● Seasonal plant

benibana, 紅花, safflower

My thanks for everyone’s understanding on the need to combine these while I catch up on things. It is always nice to receive your comments and messages, and all your thoughts are warmly appreciated. Perhaps soon, when things here settle down, I’ll have time for a good walk out in nature.

See you next kō~

[Images & info by kurashikata.com, kurashi-no-hotorisya.jp, 543life.com, and Wikipedia except where otherwise noted]

Fun fact: the breeding and raising of silkworms is called “sericulture” (養蚕, yōsan in Japanese)

The counter word for silkworms is 一頭, 二頭, etc… versus the standard 一匹, 二匹 for animals of lower station

reference: Kotobank dictionary entry

Much like how corn is unable to propagate itself without human intervention

The word “benihana” is sometimes written/said as “benibana” instead; this phenomenon is called rendaku in Japanese, and morphologically its when a consonant sound in the middle of a compound becomes voiced when it wouldn’t be on its own (so “hana” becomes “bana”)

The beni part of benihana (紅 ) means “crimson red”

The chemical pigment in safflowers is called Carthamin, and can be found on food labels today as “Natural Red 26”

In Spanish colonies, it was sometimes called “bastard saffron” due to being a cheap replacement more easily available overseas