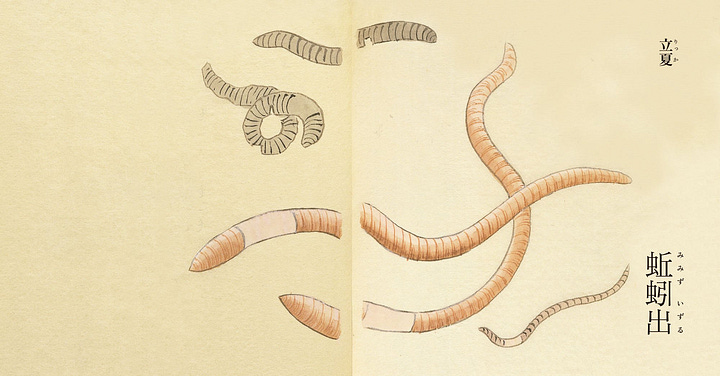

May 11 - 15

蚯蚓出

みみず いずる

Mimizu izuru

Earthworms emerge

May 16 - 20

竹笋生

たけのこ しょうず

Takenoko shōzu

Bamboo shoots sprout

The soil beneath our feet is full of life. Any given handful containing diverse microworlds. It is what we named our entire planet after, and anything that grows and thrives here is connected to it and the things that come from it. In these two kō, it is earthworms and bamboo that are unearthed.

A short, combined newsletter this time (with apologies) as I’ve spent the last week in prolonged, exhausting international transit! We should be back to normal after this now that I’m finally home.

Still, if we were to connect any two microseasons these two would be a fine choice, as they represent a cycle that starts and ends under the ground. The tunnels that earthworms burrow under the surface provide channels for rainwater to spread through the ground1 and nourish the roots of plants like bamboo. In turn, the plants that grow up eventually shed their leaves, which provide food for the worms and become a new layer of soil for them to hibernate in until the following year. A nice, healthy balance above and below.

Earthworms are called mimizu in Japanese, a name that’s said to come from 目見えず (me miezu, “unable to see”) due to their spending most of their lives in the dark and, well, lack of eyes. However, their traditional folk name shows a recognition of their valuable place in an ecosystem: shizen no kuwa (自然の鍬), or “nature’s garden hoe.” Fields and forests alike are tirelessly tilled for free by these little sightless guys.

Bamboo, for its part, needs no deep introduction. Lush, thick bamboo forests are a popular tourist destination and frequent samurai movie backdrop. But less known outside Japan are the plants proto-stage: takenoko, young bamboo shoots.

Written in this kō as 竹笋 (bamboo + bamboo shoot), the more common kanji character for takenoko is 筍, a sort of combination of the two. Another writing you may see is 竹の子, which some may recognize as using the kanji for “child.” Indeed the word takenoko literally means “bamboo’s child.” With their round, swaddled appearance and rapid growth, it’s easy to make the connection.

The reason why the young shoots’ appearance is notable enough to earn a spot in the 72 kō and common observance is primarily because they’re a delicious seasonal delicacy. In fact, one of the most famous foods enjoyed in Japan for a limited time each year. You may have already noticed, but the 筍 kanji character is made of 竹 (bamboo) and 旬 (season/10-day-period).

Thankfully, that window is a bit longer than 10 days in modern Japan: different species of bamboo grow their shoots at different times of spring and summer. Some as early as March! The native Japanese madake (真竹, Phyllostachys bambusoides) does so around this time in May. That means a few months that people can enjoy the tasty simplicity of fresh takenoko gohan (bamboo shoots on rice). Fermented bamboo shoots (menma) are also a necessary ingredient in a classic bowl of ramen.

Speaking of, let’s look at our other seasonal foods and flowers for these two kō (no earthworms on the plate, I promise):

● Seasonal fruit

ichigo, 苺, strawberry● Seasonal seafood

isaki, イサキ, threeline grunt● Seasonal flower

nadeshiko, ナデシコ, carnation

● Seasonal vegetable

takenoko, 筍, bamboo shoots● Seasonal seafood

asari, あさり, manila clam

That’s all for this time, although we’re not quite done with worms just yet! Our next kō spotlights one far more high-status than the humble, hardworking earthworm: the silkworm.

See you next kō~

[Images & info by kurashikata.com, kurashi-no-hotorisya.jp, 543life.com, and Wikipedia except where otherwise noted]

These are the 土脈 we talked about way back in Kō 4

I think it works well to combine ko whenever life gets busy. This is beautifully rendered. Bamboo Child--how lovely! 🌱