April 30 - May 5

牡丹華

ぼたん はな さく

Botan hana saku

Tree peonies bloom

Since the start of spring in the Koyomi, we've had famous trees, humble grasses, and key crops. But among hundreds of colorful blossoms, one stands above them all. Now is the time of the King of Flowers: Paeonia × suffruticosa, the tree peony.

The peak of spring in Japan brings the sights of hyakka ryōran (百花繚乱), a profusion of beautiful things all blooming at once. This can be literal, as in the case of flowers, or metaphorical, as with a gathering of attractive people or an explosion of talented achievements from a team. Kō 18 is a time to be surrounded by impressive beauty, and as much as anything the botan (牡丹) symbolizes aesthetic perfection. A flower among flowers. A platonic ideal of floral expression. I mean, just look at it:

A classic flower! Ranging from delicate pinks and whites to rich purples and crimsons—and quite large for a flower at up to 20 cm in diameter—it’s not hard to see why the intricately layered petals of the botan have been popular as both a symbol and decorative motif for thousands of years. It is the Imperial Flower of China and their unofficial national symbol1, and has been loved across the sea in Japan as well since the Heian Period (8th - 12th c. CE).

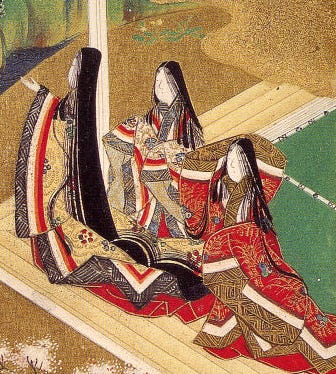

Coincidentally, this is also when the smaller island nation began to mature culturally, separate from the Chinese influence that had long dominated in formal society. The Heian is the period when Japan established its own writing systems, its own fashion, and its own artistic canon2.

What reigned during the Heian Period of Japan above all was the virtue of Beauty. And botan must have been thought beautiful enough to integrate into the newly emerging Japanese imperial culture, as the flowers appear in plenty of art, poetry, and family crests of people in power over the centuries since.3

Treated in much the same way roses have long been in Western cultures, amateur peony fanciers in Japan have also cultivated their own unique hybrids over the centuries, and it remains a popular choice for hobbyist gardeners and a crowd-drawing sight at botanical gardens. There’s even one dedicated to them in Sukagawa, Fukushima, who I can imagine are as excited as anyone for this kō.

The Heian Period is also when Japan began to embrace seasonality as an aesthetic concept applicable to more than just farming. Perhaps the most iconic example of which is the jūnihitoe (十二単), a 12-layered robe worn by noble women and styled to reflect the naturally beautiful colors and shapes of nature as the seasons changed. At this point, the Koyomi and its microseasons had been in Japan for around 200 years, so one can easily imagine it being consulted by those hoping to be perfectly on-peak in their coordination.

We mentioned the importance of names in Kō 16, and the concept of kotodama-shisō when it came to homonyms for the useful riverside reed. This is a nice time to revisit that, because botan is part of a secret flower language that flourished during this time and remains in use today. I’m not talking about how to use a bouquet to secretly tell someone you hate them, but about meat.

You see, the eating of meat4 has been banned at various points in Japanese history, spanning a total time of around 1,200 years, on and off. In 675 AD, the Buddhist Emperor Tenmu issued the "Imperial Decree Banning Meat-Eating" and it remained in full effect during the Heian Period, prohibiting the slaughter and consumption of all types of game and livestock. Of course, strict edicts issued from on high rarely reflect the needs and desires of the common man, and people do what they need to survive.

For those living in mountain villages far away from the capital—and, more importantly, far away from the ocean—the emperor’s wish for his subjects to subsist on seafood was untenable. To avoid punishment both governmental and spiritual, a bit of linguistic creativity was needed. Enter: ingo (隠語), literally “hidden language.”

But what does this have to do with the beautiful pink layers of the botan flower? Here’s a plate of boar meat, ready for a hotpot:

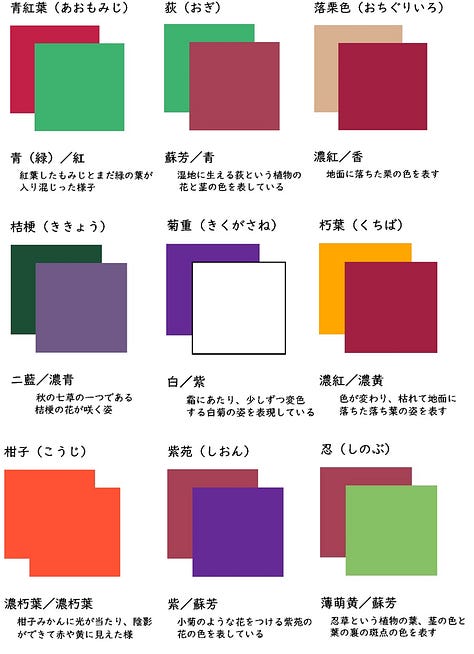

It’s said that the thin-sliced boar meat, when layered on a plate, resembled the pinkish-red botan flower, so the name came into use during the prohibition. While boar was the most common (and nourishing) game meat available to people in the mountains, other meats received similar botanical nicknames:

sakura (cherry blossoms) for horse meat, due to the light, marbled pink of certain cuts

momiji (maple leaves) for venison, due to their being featured together on October’s hanafuda cards and overall autumn motifs

kashiwa (oak) for chicken, since the fallen leaves are a similar color to the meat when cooked

ichō (ginkgo) for duck, since the yellow matches their beaks and feet

Many of these are still in use today, if anything else because that’s how they spent 1,200 years being referred to and these things tend to stick after a while. As for beef and pork? Those aren’t natively bred in Japan, and weren’t commonly eaten until the Meiji Era, when meat-eating prohibitions were eased.5

One last Botan to mention—this one:

From the 1990s manga and anime series YuYu Hakusho, the character above is named Botan, and while the pink robes are certainly a color match for our peonies, there’s a different reason for her name. In the series, Botan is the Grim Reaper, ushering the dead to the spirit world. When asked, the author said he associated botan flowers with ghosts, and he’s not the only one: in Japan, there’s a popular ghost story called “The Peony Lantern” (Botan Dōrō, 牡丹燈籠) which involves a supernatural love between a widower and the ghost of a beautiful woman (it’s actually sweeter than it sounds, although spooky). The titular lantern was the one she carried when they met, patterned with peony flowers.

As with many important cultural symbols, there’s plenty more to say and show about the botan’s prevalence in Japan, but let’s talk for a moment about tea. Last time, I mentioned the Eighty-Eighth Night, which is 88 days from the start of Risshun, when spring officially begins by the Koyomi’s counting. Hachi-jū-hachi ya (八十八夜), as it’s called in Japanese, is the time when the weather is considered to be generally safe from cold snaps and sudden frosts that can damage young plants. Farmers have long used the date as a yardstick for when to plant things like rice seedlings, but in modern Japan its most significant impact is in enjoying the season’s first tea harvest.

This first flush of tea leaves are considered to be the highest quality you can get, and if you’re in one of the tea-growing regions of Japan6 you can watch (or participate) in picking or hand-rolling freshly harvested leaves. Or simply sit down with a cup of shincha (新茶), literally “new tea” and savor its pure, verdant aroma. It’s also said to be full of beneficial nutrients essential to long life and preventing illness. This season only lasts for about two weeks7, so if you have a chance get out there!

If you’re having a cup of tea at peak-season, you’d do well to search out some accompanying sides, don’t you think? Here’s the Kō 18 highlights:

● Seasonal vegetable

kogomi, こごみ, young fiddlehead fern● Seasonal seafood

sazae, さざえ, turban shell● Seasonal flower

botan, 牡丹, tree peony

For Japan, the microseasons are shifting out of the more dramatic winter-spring changes and into a period of growing warmth and daylight. When you’re in the middle of a season, things feel stable and (hopefully) peaceful. While spending time in nature these days, you may not notice as many differences to a week prior, but that in and of itself it something worth noticing, I feel. A little calm and familiarity is never a bad thing after a transition, especially with hundreds of flowers in bloom.

See you next kō~

[Images & info by kurashikata.com, kurashi-no-hotorisya.jp, 543life.com, and Wikipedia except where otherwise noted]

Thank you for 100 subscribers!! It’s very surprising and humbling to see you all here and that you’ve shared this with others. I hope you’re enjoying the reads and learning something new!

On paper, it’s the plum blossom, but this continues to be debated despite various government decrees

It’s during the Heian that two hugely influential works—The Tale of Genji and The Pillow Book—were written, both by women

The Imperial Flower of Japan is not the botan, but the kiku (菊, chrysanthemum)

Excluding fish, which even modern Japan considers separate to animal-flesh-meat (vegetarians beware!)

Even now, pork is far more common (and cheaper) than beef and the large amount of flat, open space required to ranch them

Saitama, Shizuoka, and Kyoto

About the same length of time the botan blossom, as it happens

I was not expecting to see Botan from YuYu Hakusho, but happy to see a familiar face. I learned so much from Kō 18 🌸