This is the start of 72 Microseasons, a newsletter about Japan’s ancient almanac and its tiny, poetic seasons

A fresh, warm start

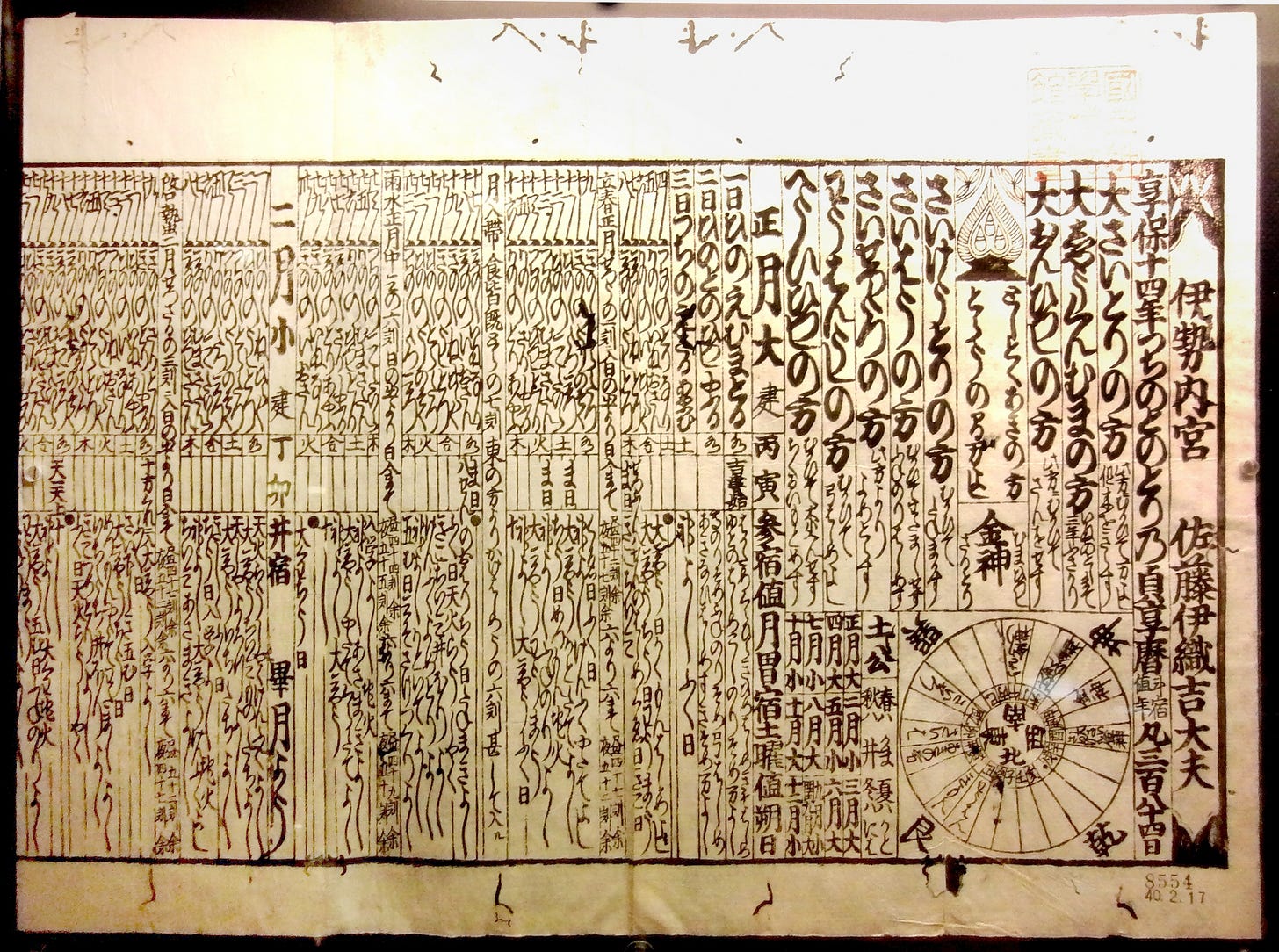

February 4th marks the start of Japan's ancient calendar/almanac, the Kurashi no Koyomi (暮らしの暦, lit. lifestyle calendar). Which, rather than standard Gregorian weeks, is measured out in 72 "kō" (候)—what we in English have taken to calling "microseasons."

Nowadays, it's regarded as something of trendy-chic curiosity, with apps and Aesthetic™ desktop calendars, but I find its concept of measuring time according to what you see around you enduringly interesting. After all, don't we still more or less do that? (See Wellington's Realistic Calendar, with its periods of Shitsville and false spring ‘Spring 1’) We track our work, responsibilities and commitments via days and weeks, but it's by those changes to our surrounding environment that we really "feel" the passage of time. When we’re looking to the week ahead, we check the weather. Our days are filled with comments on the breeze, the color of the grass, and the birds and bugs around us.

A while back, I tried running a Twitter account tracking these "microseasons" but, you know, Life. Since then, I’ve been thinking about a place for this project, where I could write a bit more and there's potentially folks who would find this intersection of history, language, nature, and culture interesting. So…here we are!

If that’s maybe your jam, then stay tuned for Kō 1: "Spring Winds Melt The Ice" coming up right after this.

But first, a quick introduction on The Kurashi no Koyomi and its seasons:

As mentioned, the microseasons (kō) are 72 individual periods of roughly 4-5 days. These are grouped into threes to make up 24 lunisolar terms called “sekki,” which are about half a standard month long, give or take.

The microseasons were originally conceived of in China (around 100 BCE, with the 24 lunisolar terms even earlier—around 400 BCE) and rooted in the natural phenomena of that country’s environs and climate. First adopted around 600 BCE, Japan eventually (~1,000 years later) changed and shifted their calendar to match the flow of their own natural surroundings and reflect the Pacific island’s unique flora and fauna.

These changes were made by one Shibukawa Shunkai (渋川 春海), a man with an appropriately nature-friendly name who not only localized the Koyomi, but was also Japan’s first government-appointed astronomer and a mean Go player. While he was at it, he also corrected a bunch of longstanding inaccuracies and correctly calculated a solar year to be 365.2417 days.

The new Japan-centric Koyomi found increased popularity among common folk, being better connected to the realities of their day-to-day, and was in use for around 200 years (1685 - 1873) until the Meiji Restoration brought in the Western Gregorian calendar as the new standard.

Anyway, the National Diet Library of Japan has a good, in-depth history about the Koyomi and Japan’s other calendars if you want to really dig in, but for now let’s leave things here.

See you next kō~